Give Me More Medium Form Content: Enter the Riff

TLDR: As short-form content continues to dominate social media, an appetite for mid-form content has emerged. I discuss the “riff” as my favorite form of such content–a mix between technical and entertaining, engaging but short enough for a single reading session. I talk about how social media has warped our concepts of what “successful” content looks like and why writing online can have more value than you think.

Personal writing serves as a funnel for like-minded individuals. That’s why this site exists! Despite a pretty limited digital reach, I’ve been able to connect with lovely people I’ve never met in-person because I’ve either built or written publicly. I definitely benefit from a funnel. I have a broad number of hyper-specific niches I follow that I normally wouldn’t get to engage with others on: specific topics in virology, scientific coding, data science, and ballet. As I’ve slowly acclimated to creating online, I’ve thought a lot about how to achieve this effect–to build relationships with cool people–using my writing.

Enter The Riff

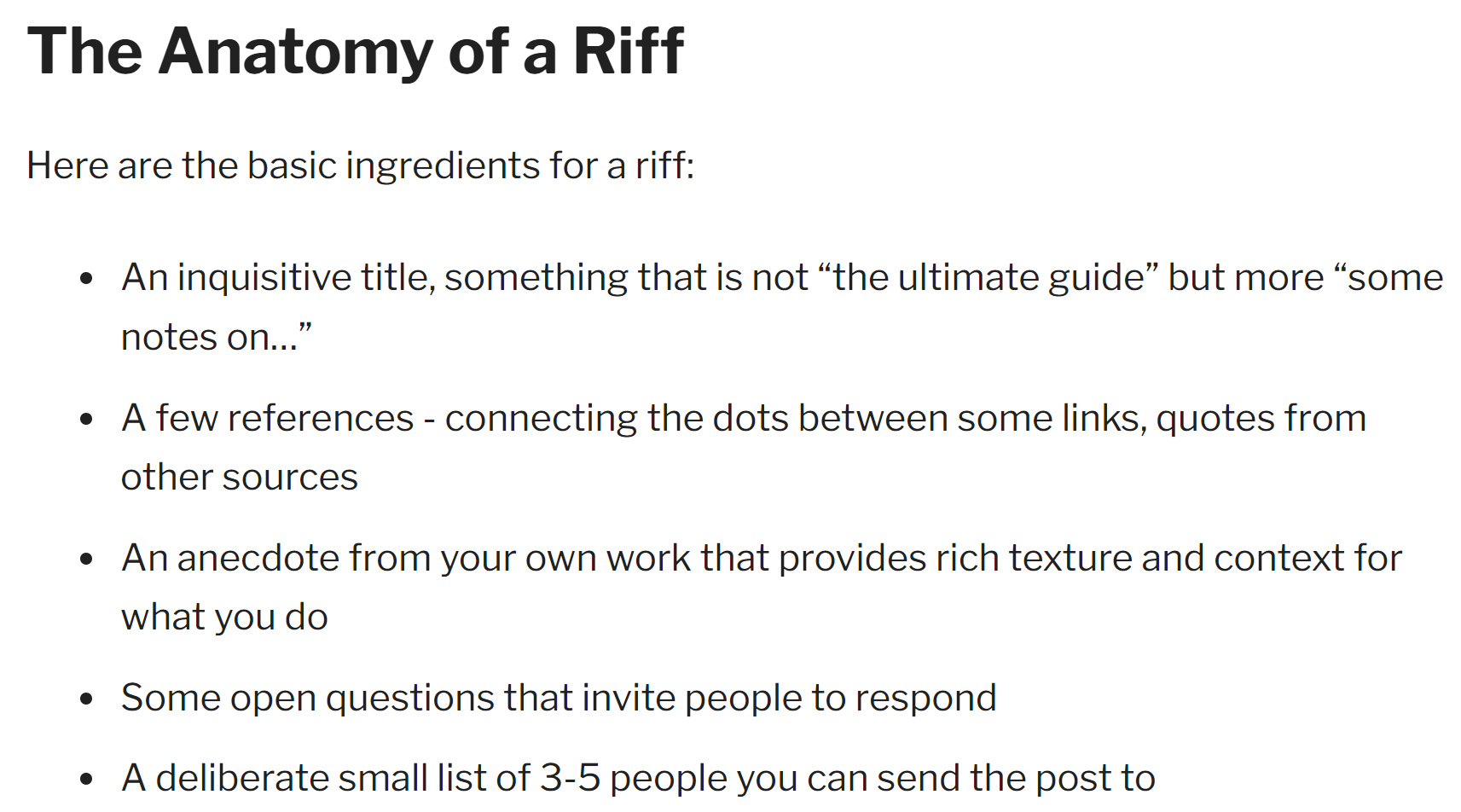

On the internet, there is a particular format I adore reading and writing: the riff. I’ve only seen this term in reference to a structure described by Tom Critchlow in Writing, Riffs & Relationships. Here are his parameters for a riff:

Riffing About Riffs

The riff isn’t written for consumption by all audiences - it has limited accessibility. It communicates at the level of a specific group or is even written with a specific person in mind. A riff is not inherently about entertainment but it also isn’t a tutorial. The best riffs balance being sufficiently technical but also generalizable to a broader story. They aren’t a cognitive slugfest though they introduce several ideas. I’m hoping to write a riff here to demonstrate.

My belief in the riff as the ideal format for mid-form content is part of an ongoing reformation of how I use social media. Conscientious, slow consumption of media to un-cook my brain. Where social media posts aim to maximize time on their platform via countless short-form bits of info, the riff is often hosted off-platform, requires minutes of sustained attention, and overall displays qualities antithetical to social media churn. Twitter/Bluesky/Mastodon threads are great for discoverability but they intentionally make it difficult to create a full-blown riff: word limits, very basic linking of references/citations, and no footnotes. While still possible to riff in a thread, more and more creators are using platforms like Substack or self-hosting content.

Despite my appetite for the riff, most scientific writing I encounter on the internet is not written this way. Barring links to journal articles or pre-prints, the majority of science writing I see in biology-related disciplines are in the form of lone, stray comments or brief paper summaries that really focus on communicating a few takeaway points. Technical blogging and riffing are much more abundant in computer science, machine learning/AI, and some bioinformatics spaces.1 It is embedded in these fields’ culture to share code, build in public, and discuss experiences much more irreverently. Blogs abound. The chronically online, 10x software engineer aspirants write to be the next Paul Graham and with good reason.

So, who in biology are the riff-makers? Dr. Eric Minikel’s blog is as good as it gets, integrating the science behind his work with wife/collaborator Dr. Sonia Vallabh and their personal journey to cure prion disease. Arcadia Science (particularly their icebox) is interesting as a case study in alternative funding models in science. For virology, I will read any Ryan Hisner tweet thread on coronavirus biology (@LongDesertTrain on Twitter) and find myself engaging more and more with Isabel Ott’s content (@isabelott.bsky.social on Bluesky). For more polished enterprises with broad reaches, episodes of Dr. Vincent Racaniello’s immensely popular podcast This Week in Virology have the makings of a riff as do the Substack posts of Dr. Eric Topol.

So Why Don’t We See More Riffs In Biology?

Part of the riff’s scarcity is how scientists are trained to write. We are told to be formal, not too idiomatic, and not too speculative. Beyond my own appreciation, there’s definitely an appetite for quick, dirty riffs filled with hefty, hefty hand-waving and conjecture. When presenting findings to colleagues or chatting about work with friends, the verbal analog of the riff are among my most energizing conversations: “What if these two ideas are connected?”, “I know this obscure tidbit that might be related…”.

I also suspect the same reasons I was personally put off from social media for so long are at play. Fear of over-sharing. Fear of wandering outside of one’s expertise. Fear of nothing to say. I’ve used “fear” but my anxious mind perceives these as very sensible concerns. Surely, some individuals must be incredibly particular about messaging and accuracy. Writing and putting yourself out there on the internet requires a degree of self-importance for sure. The transparency of writing leaves one vulnerable. “I can’t be so publicly wrong and intellectually mediocre.” Though I still experience these concerns, I’ve been able to put them aside and continue sharing in public in a way that makes me happy. Not everything need be a well-crafted masterpiece. That’s the beauty of riffing.

Another idea is that riffing is a lot of work for little pay off. Well, it is indeed quite a bit of work.2 However, I think the benefits of personal blogging and riffing are underrated. You are free to write in a way that is historically undervalued in academia.

Consider this excerpt from Alexey Guzey’s blog post Why Have A Blog? before it 404’d:

“Academics gain prestige by publishing novel stuff. This gives them a warped perspective on what is valuable. You can’t publish a paper that would summarize five other papers and argue that these papers are undervalued in a top journal but in the real world the value of doing that might be very high. The mechanisms of discovery are broken in academia.”

The indie and personal web are resurging, hearkening back to our internet roots–when we had MySpaces, Geocities, or Xangas (what got me started learning html and eventually coding). Hosting on the independent web provides a disconnect from the metrics of engagement: likes and reshares. For now at least, I take solace in the fact that many people won’t read or engage with my writing. The idea of going even remotely viral (moreso the scrutiny that entails) makes my heart race and palms sweat. As an academic, I’ve become comfortable3 with the idea that the majority of work I produce will have a limited audience. Yet, some readers may internalize my work and be influential enough to build on it. Put it this way: having one hundred people read and intellectually engage with your post may be modest by social media standards but is excellent by scientific research article standards.

I think the title of this post communicates what I want out of writing this. Write a riff. Send it to me! It is a low-stakes experiment that has surprised me with how positive the results have been. Any riffs you adore? Send them along too.

MD-PhD Student at University of Texas Medical Branch

I write about viruses, data science, and ballet.

Click home at the top of the page to see other things I’ve been working on.

jayeung@utmb.edu

Footnotes

Sometimes controversy happens in the blogosphere. What other format would you even publish such writing in?↩︎

I spent roughly 5 hours on this. But! I beg you, do not flood the internet with low-effort, ChatGPT generated garbage. We can tell. 👀↩︎

Or resigned to..?↩︎